Sparks and Sherrie with extended family

A. Sparks and Sherrie Sparks

Masto Foundation

When I was 12 years old, I was with my mother and Auntie Tami (Tamiko Tai, who was at Minidoka for the full duration of the war) at the Washington State Fair in the Puyallup Fairgrounds. As we were walking through the "Merchants Building" amidst the booths where vendors were selling food processors, massage chairs, and fancy mops, I remember my Auntie casually saying, “Oh... this was our barn." I was shocked since, prior to her comment, I wasn't even aware of the Puyallup Detention Center. But I was also shocked by the disconnect. Standing there amongst the kitchen gadgets, where thousands of people were unlawfully and unjustly imprisoned, my Auntie alone held on to the memory of a history that was lost.

Over the years, as I dug deeper and learned about the incarceration, I tried to get my Auntie to talk about her experience. She would talk about the showers and the food. She would talk about how dusty it was or how it was freezing cold at night in the winter at Minidoka. She would never talk about her outrage or the injustice or the grief she felt by having to uproot her life (where she was actively enrolled and set to graduate from the University of Washington, in the 1940s, as a Japanese American woman!). This was hard for me to understand.

When I entered college and started to chart my own path, I felt an incredible amount of excitement for the future, knowing that I could follow my dreams and do anything. But the stark contrast with my Auntie’s experience in her college years also left me with a sense of sorrow. Her dreams were stolen. Any optimism she had for the future -- all her hopes and aspirations were robbed. The loss was unfathomable.

Over time, and as my family members passed away, I began to have a deeper understanding. I realized that my path started long before I was born. My ability to make my own choices — to protest, and to fight against injustice was gifted to me by my ancestors. Their silence was out of necessity and allowed them to preserve. Separating emotions was a means of survival. Their choice to move forward and adapt laid the foundation for my future.

I asked my Auntie once, “How could this have happened? Why didn’t you resist?” and remember her saying, "They had guns. What the heck were we gonna do about it?… We had to go."

My Auntie Tami and our family members who were at Minidoka are gone now but time and their sacrifices have given us an opportunity. They struggled in silence but we can fight on their behalf. We can share their stories. We can honor their memory and resilience by not allowing their history to be erased.

Masto Foundation is committed to preserving, protecting, and educating future generations about the injustice of WWII incarceration by investing in the Minidoka National Historic site. We invite you to join us by making a one-time donation or a multi-year gift that will support the work of Friends of Minidoka for years to come.”

-A. Sparks

To learn more about the Masto Foundation:

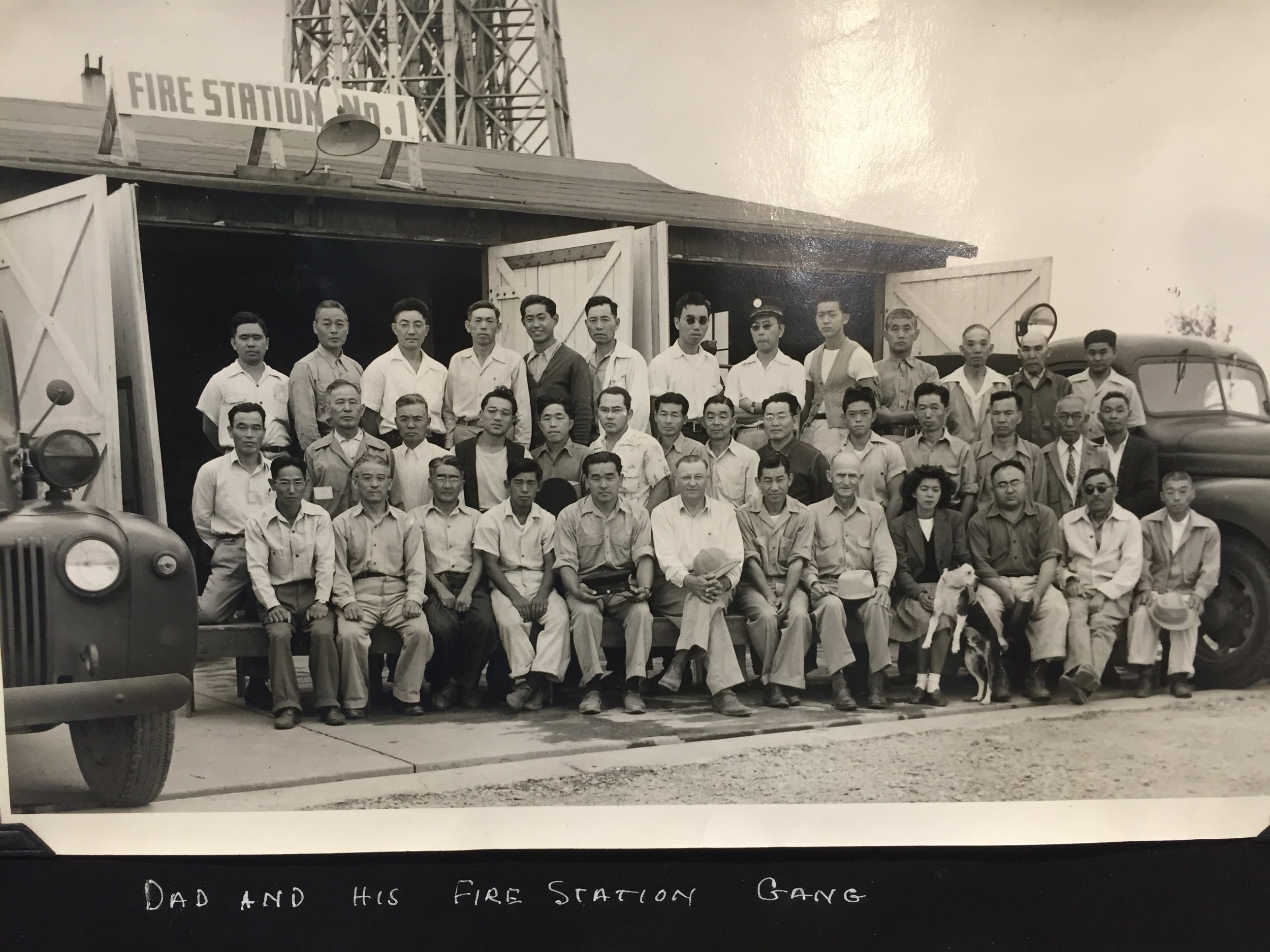

Harry and Masie Masto worked at a farm labor camp during incarceration. When Sherrie was an infant, they visited family at Minidoka. Fire Station group photo: Nobuyuki Yokoyama, Sparks’ great grandfather, second row, third from the left. Harry, Masie, and Sherrie at the farm labor camp. Photos courtesy of A. Sparks.